by Nate Suits

When disaster strikes, when systems fail, or when communities feel abandoned, it’s the collective efforts of individuals that weave the fabric of resilience. It doesn’t require grand gestures or sweeping policies; it begins with the simple, profound truth that when we unite, we can achieve more than we ever could alone. Whether it’s rebuilding after a storm, reviving a forgotten corner of a neighborhood, or addressing the struggles of daily life, collective action is the thread that binds us, making us stronger and more connected.

If we want to build better communities, collective action must become more than just an occasional response to crises; it must become an unconscious behavior within society. The ability of individuals and organizations to work together toward shared goals is essential for addressing our complex social, economic, and environmental issues. However, coordinating such efforts requires overcoming significant obstacles, including limited resources, varying priorities among stakeholders, and the complexities of effective communication. These challenges are further compounded by the need to build and sustain trust, ensure equitable participation, and adapt to the rapidly changing demands of our modern societies. Collective action is the outcome of solving complex coordination problems in our immediate environments by uniting communities around shared goals and aligning their efforts through collaboration and mutual accountability.

Currently, we rely on our institutions of government to facilitate this collective action on our behalf through bureaucratic forms of public administration. In our daily lives we rely on our local governments to solve a myriad of problems ranging from the provision of essential social services to maintaining our fragile and degrading infrastructures.

A significant barrier to the continued efficiency of our centralized public-sector is the limited capacity that local governments have to monitor and execute the policies adopted by the citizens of their respective jurisdictions. Additionally, the financial and human capital within these centralized structures are not well equipped for the adaptation of the ever-growing needs of the local population. As we continue to see the stress that our local governments are under, we must come to the realization that our modern-day administrative methods for collective action are not and will never be sufficient.

Our reliance on government institutions has allowed us as individuals to be as free and creative as we can be, knowing that we do not have to worry about providing these things for one another. However, this reliance cannot be maintained without public trust; trust that our tax dollars are spent wisely, and trust that those with the power to make decisions on how our tax dollars are spent do so ethically and with precision.

While we have a lot of bureaucratic mechanisms in place to preserve that trust, we often see the degradation of these accountability structures in many of the institutions and agencies within our local governments. Public trust is the metric of survival for all governments, and when that public trust erodes we see how fragile our society becomes. As we strive to expand our government’s capabilities to ensure this trust is never broken, all it takes is one bad actor to destroy everything we’ve worked so hard to build.

The growing distrust in centralized institutions combined with the increasingly complex demands for their work requires a swift reimagination for how we facilitate collective action in the 21st century. In order to do this, we need to do more than criticize and attempt to destroy our current methods of public administration…we need to provide alternatives.

Decentralized Public Administration Networks (dPAN’s)

The use of distributed ledger technologies is a fundamental advancement within the category of coordination. While the majority of blockchain innovation has been centered around the financial mechanisation of everything, its applications within the area of human coordination have been extremely limited. While there are many reasons for this, ranging from a lack of funding to issues of liability, the largest obstacle has been establishing a vision and framework for how blockchains can be utilized for the purpose of facilitating local collective action.

Fundamentally, blockchains provide us with permanent pieces of digital public infrastructure that can be relied upon even after it stops providing us with meaningful utility. Blockchains inherently minimize the need for trust, and create robust incentives that can be fine-tuned to influence the formation and conditioning of new types of communal behaviors. Additionally, they offer an environment for repeated games to be played where acts of civic engagement through repetitive functions can lead to norms of reciprocity that improve the efficiency of society and facilitate coordination without the fear of corruption or exploitation.

A decentralized Public Administration Network (dPAN) is a local blockchain network that is designed to incentivize the coordination of local citizens and organizations around a specific set of collective functions. The purpose for creating these networks is to shift public trust away from government agencies and place it into equilibrium with the citizens it represents by giving local communities the tools by which they can become self-reliant. The thesis being that by atomizing the mechanisms of public administration, coordination networks can unlock a more inclusive, democratic, and cost-effective path for community lead governance, enabling a more direct and responsive means for facilitating collective action that serves as a more viable and sustainable alternative to traditional public administration frameworks.

dPANs consist of nodes within a local POA chain that are hosted by non-profits and government agencies, and execute a wide-range of decentralized applications (dApps) which attempt to mimic government functions. There are two (so far) fundamental types of public administration applications within these networks:

Functional Applications

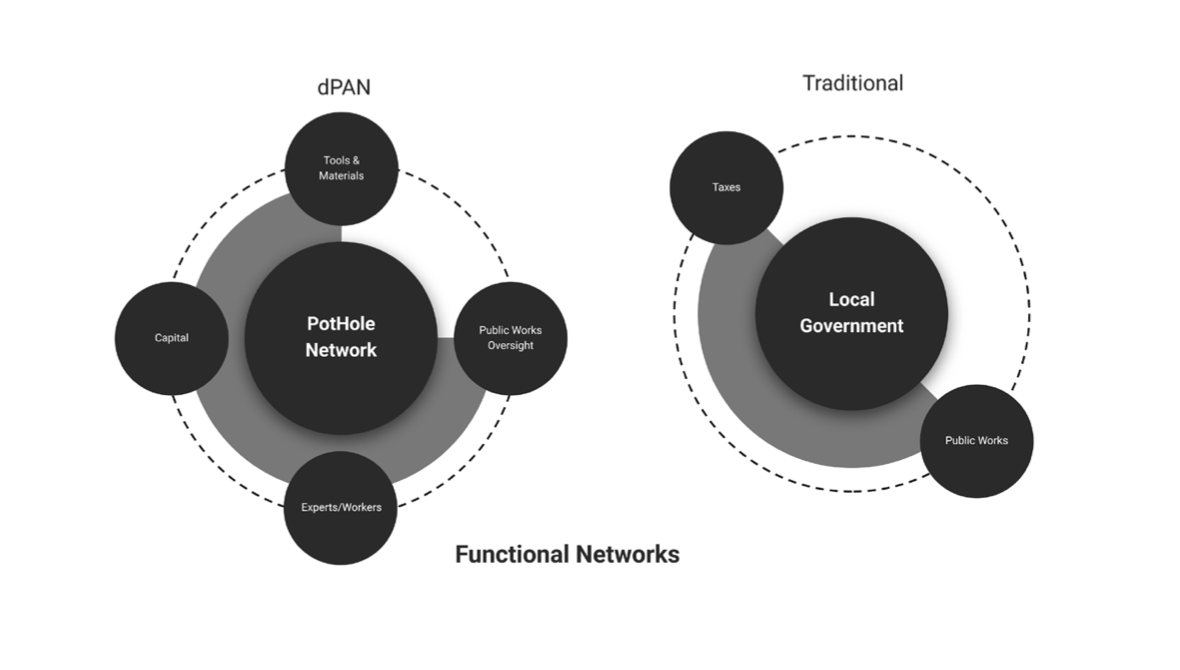

These applications are designed to coordinate and execute the provision of public goods and services traditionally charged to our local governments. This includes activities such as road repairs, city cleanups, emergency response, community programs, park maintenance, etc.

Example: PotHole Network

Imagine a city where potholes are no longer an enduring frustration, waiting months or even years for repairs due to bureaucratic bottlenecks and funding constraints. Instead of relying solely on tax-funded public works departments, the city implements a decentralized Public Administration Network (dPAN) dedicated to road maintenance. This network operates on a simple yet powerful principle: direct coordination between those who use the roads, those who repair them, and those who are able to supply the necessary materials.

In this model, residents and businesses who rely on well-maintained roads contribute directly to a crowdfunded pool, each contributing a small, voluntary amount proportional to their usage. These funds are then allocated through a decentralized system that prioritizes road repairs based on real-time community input. Contractors and road maintenance professionals register with the network and bid on repair projects, ensuring efficiency and competitive pricing. Material suppliers integrate directly into the network, streamlining procurement and reducing waste.

Now, contrast this with the traditional public administration approach. In a conventional system, road repairs are funded through taxes collected by the local government, which then allocates a fixed annual budget to the public works department. The department, constrained by limited resources and bureaucratic inefficiencies, must prioritize which roads to fix, often leaving smaller but heavily trafficked streets neglected due to budgetary restrictions. The process is slow, top-down, and often unresponsive to the real-time needs of communities.

With the dPAN model, the local government shifts from an active agent to an overseer, ensuring quality control and regulatory compliance rather than managing every aspect of road maintenance. The result? A more agile and responsive system where far more roads can be repaired in a given time frame, communities have direct influence over infrastructure improvements, and funding is allocated efficiently to maximize public benefit. By decentralizing the decision-making process and removing bureaucratic barriers, this approach transforms a long-standing coordination problem into a dynamic, self-sustaining solution.

Structural Applications

These applications are designed to reorganize the way in which governments, organizations, and citizens interact with one another. This includes activities such nonprofit funding, voting, health services, volunteer networks, homeless services, permits, etc.

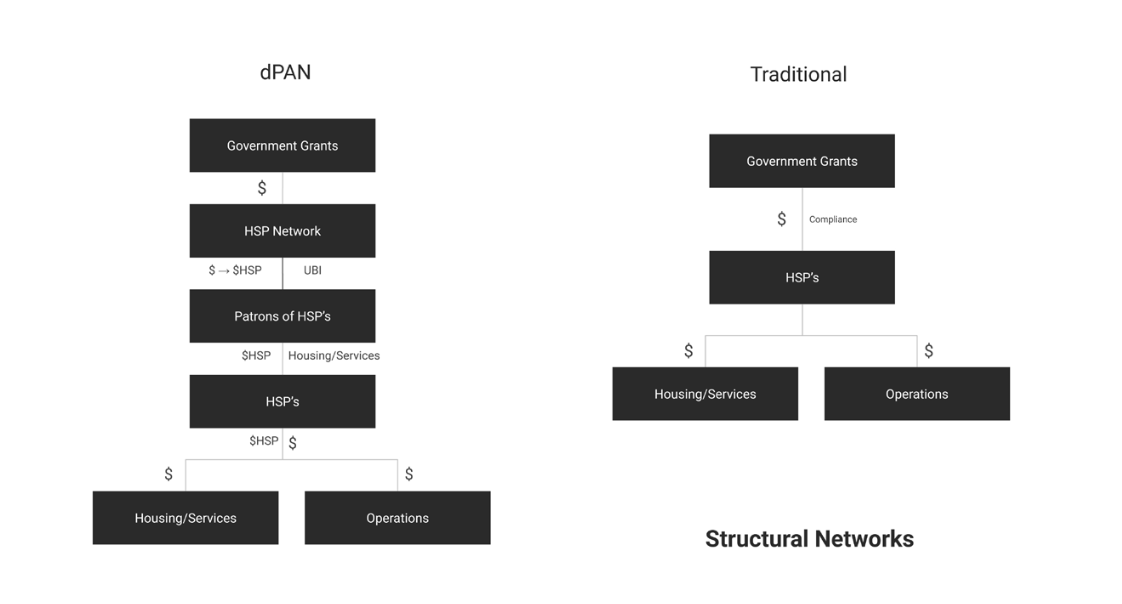

Example: Homeless Service Providers

For decades, cities have struggled to provide consistent, effective solutions for homelessness. Traditionally, Homeless Service Providers (HSPs) operate as independent nonprofits, each vying for limited government grants. These grants come with rigid financial oversight, dictating exactly how funds can be spent and restricting the ability of these organizations to implement innovative solutions. As a result, HSPs spend as much time competing with one another for funding as they do serving the homeless, creating inefficiencies and limiting their collective impact.

Now, imagine an alternative—a decentralized Public Administration Network (dPAN) designed to change the way funding flows between governments, service providers, and the homeless community. Instead of issuing individual grants to a fragmented network of nonprofits, the government funds a single HSP Network. This network then distributes funds directly to the homeless population in the form of a basic income that can be spent at participating service providers.

This structural shift fundamentally changes the incentive landscape. Under this new model, HSPs no longer compete for government grants; instead, they compete to provide the best possible services to attract and retain the patronage of the homeless individuals they are dedicated to serve. With the autonomy to experiment with their resources, HSPs can develop more responsive and effective programs, whether that means expanding transitional housing, improving mental health services, or offering job training programs. The result is a more dynamic and demand-driven ecosystem, where services align with the actual needs of the homeless community rather than the prescriptive constraints of grant agreements and public service strategies.

By decentralizing funding and shifting control closer to those directly affected, the HSP Network restructures the way homelessness is addressed in cities. The role of government shifts from dictating service models to providing funding, allowing HSPs the flexibility to expand their services and focus on the needs of the homeless. This transformation turns a system of scarcity and competition into one of abundance and collaboration, demonstrating the power of structural dPANs to redefine public service delivery for the better.

While these categorizations are a broad attempt to describe the design space, the types of potential applications are limitless, and can be tailored to fit the needs and context of the local community initializing the effort. Since these applications can be open-sourced, the successful implementation of a network application in one city can also be provided as a solution for another, in essence, creating a marketplace of administrative solutions that can shift the role of local governments from an active agent in our communities to that of an overseer.

The continued development and experimentation of local coordination applications has the potential to transform collective action from a highly rigid, reactionary process (via government) to a highly adaptable and anticipatory process (facilitated by citizens). If these types of coordination tools can be utilized in a manner that incentivizes and rewards citizens for their civic engagement, we can begin to build the foundation for a highly anticipatory civil society.

Additionally, decentralized Public Administration Networks (dPANs) introduce a competitive alternative to traditional local government service provision by leveraging efficiency, transparency, and direct community engagement. Unlike bureaucratic government agencies bound by political cycles, budgetary constraints, and administrative inertia, dPANs operate with agility, responding dynamically to local needs through decentralized coordination and incentive structures.

The use of new allocation funding mechanisms can enable dPAN’s to create a system that shifts the dominant sources of coordination capital from a taxation-based process via government to a voluntary or algorithmically distributed process through citizen contributions based on necessity. Over time, as these networks prove their ability to deliver superior services at lower costs, they can gradually absorb more administrative functions, allowing local governments to transition into light-touch oversight roles. If scaled successfully, dPANs could redefine local governance, replacing hierarchical government structures with self-sustaining, community-driven networks that provide essential public goods more effectively, ultimately transforming governance into a decentralized, participatory system tailored to the needs of its citizens.

Back to Table of Contents | Next: From Information Tsunamis to Local Streams: Rebuilding Community News to Protect Democracy | Previous: Neighbourhoods