By Andrea Farias

In Barcelona, Spain, we’ve lived with drought since I settled here in 2020. Our reservoirs hover around 30% capacity, even after recent devastating floods that ravaged nearby coastal cities, throwing cars around like toys and tragically claiming hundreds of lives. Every summer, we fear running out of water… and every summer, the solutions proposed feel increasingly desperate.

In a move fit for political satire, officials have proposed to address this crisis by shipping in tens of millions of euros worth of water by boat. While our local government genuinely wants to address this challenge, they operate within systems that limit both thinking and action. Water management is fragmented across political boundaries that ignore ecological reality of watersheds, while bureaucratic structures restrict responses to a narrow set of solutions - more infrastructure, more control, more engineering.

Change is blossoming through a growing movement of people relearning how to organize human activity around ecological rather than political boundaries. These bioregional organizers are pioneering a fundamental shift in how communities operate within their local ecosystems. Their work happens through both ecological projects, like watershed restoration, and the careful work of bringing people together through new forms of community building and governance.

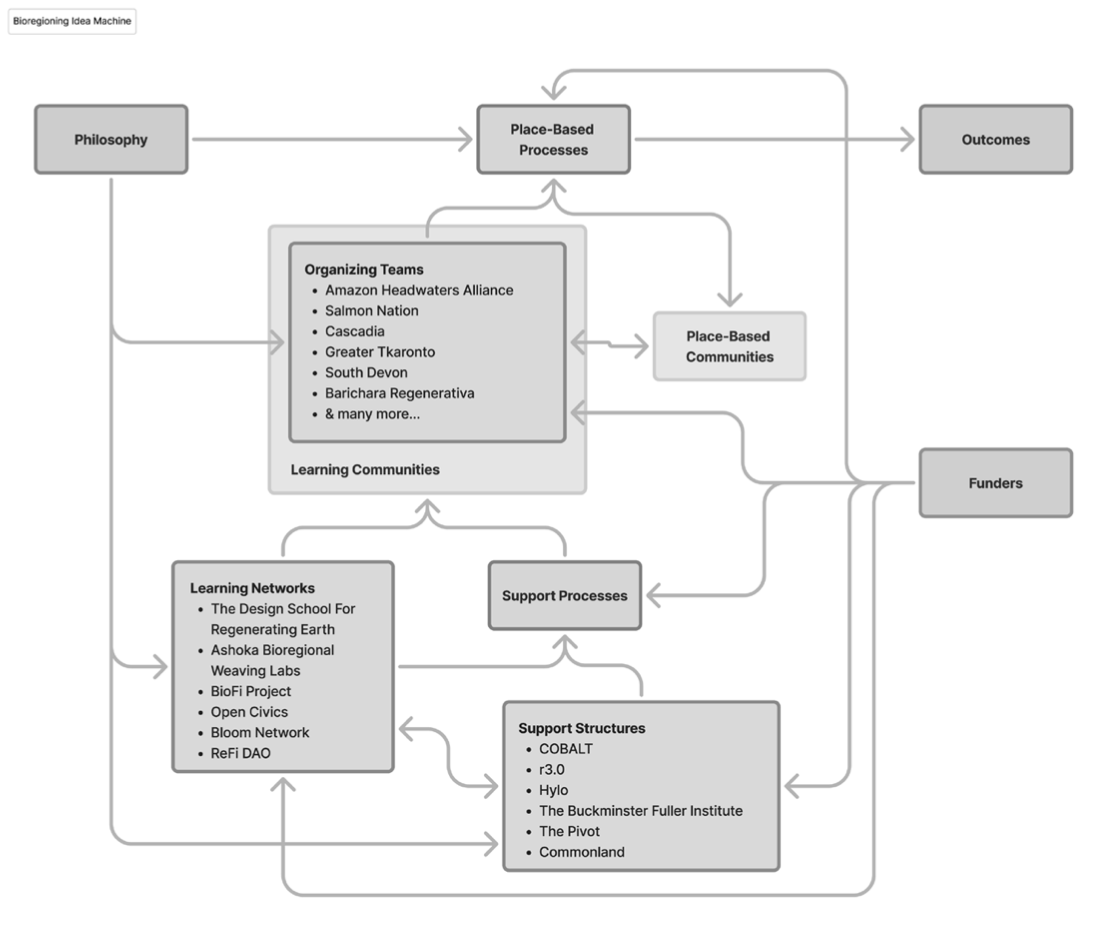

The bioregional movement operates as an interconnected ecosystem with three key elements working in dynamic relationship: bioregional organizing teams working directly in their territories; learning networks and support providers creating infrastructure for knowledge sharing and capacity building; and broader players such as funders that play a crucial role in supporting bioregional work.

This diagram is loosely based on Idea Machines by Nadia Asparouhova.1

At its heart, bioregional organizing is grounded in a philosophy of ecological embeddedness - moving beyond treating ecosystems as resources to be controlled and instead developing a deeper ecological consciousness that lets living systems guide human activity. This represents a fundamental shift from the mechanistic approaches seen in conventional resource management. Instead of responding to water crises with expensive and energy-intensive technical solutions like transporting water, ecological embeddedness works to restore right relationship with natural systems.

This ecological consciousness manifests in three key ways:

Bioregional organizing is inherently process-centric, recognizing and working to support the dynamic flows and cycles of life - from salmon runs to seasonal water patterns to wise capital allocation.

It operates with a fractal structure, where patterns of organization repeat and adapt across scales, enabling appropriate governance to emerge at each nested level, from neighborhood to watershed to bioregion.

It is plural in both knowledge and practice, making space for multiple ways of knowing and being, and recognizing that boundaries are often fluid rather than fixed.

This philosophy is translated into local action by bioregional organizing teams – groups working to coordinate regenerative activities within their bioregions. These teams implement place-based processes to maintain healthy ecosystems while meeting human needs. This includes both ecological regeneration and organizational processes – the essential activities of bringing people together and coordinating resources. Some examples of bioregional organizing teams are pictured in the map below.

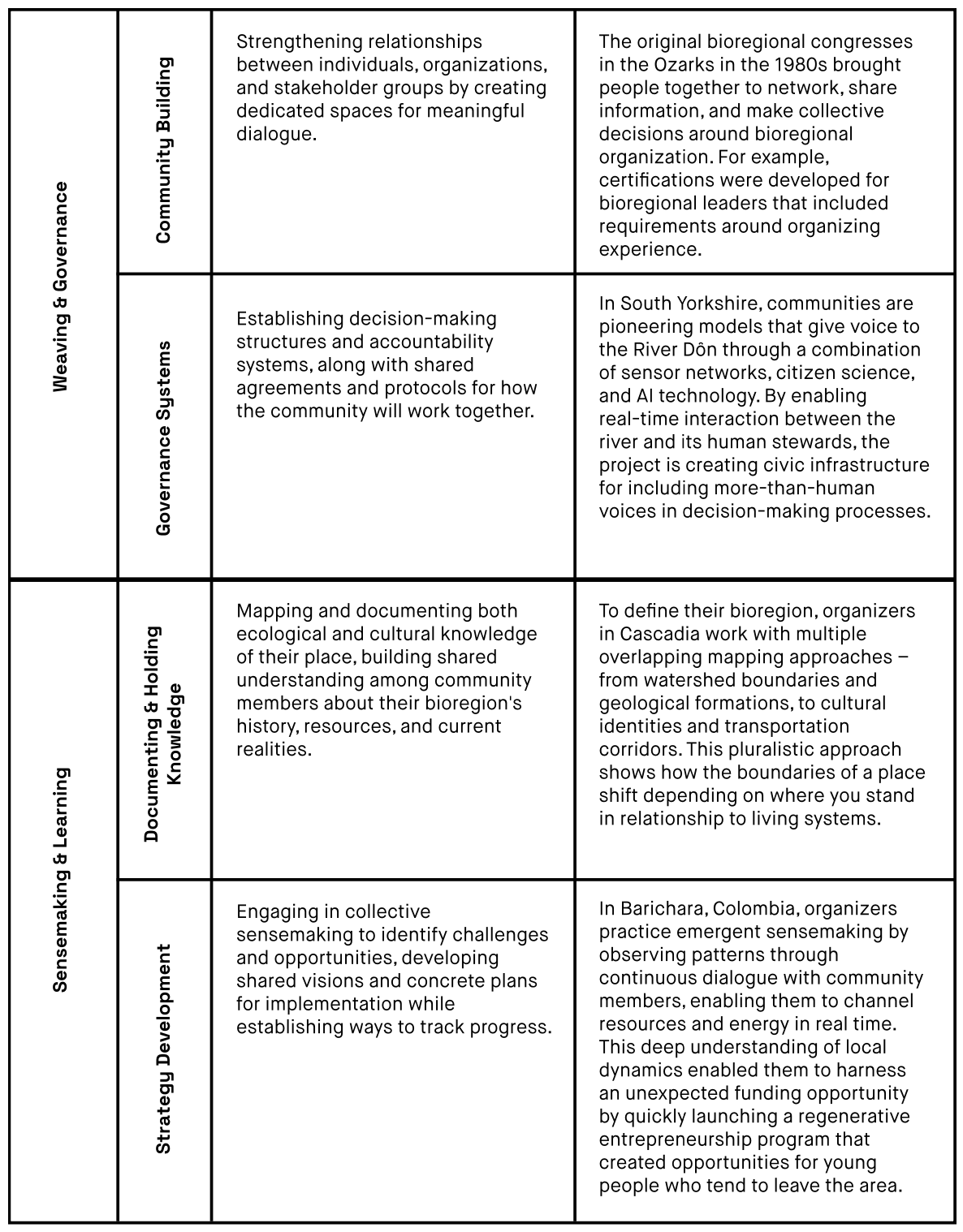

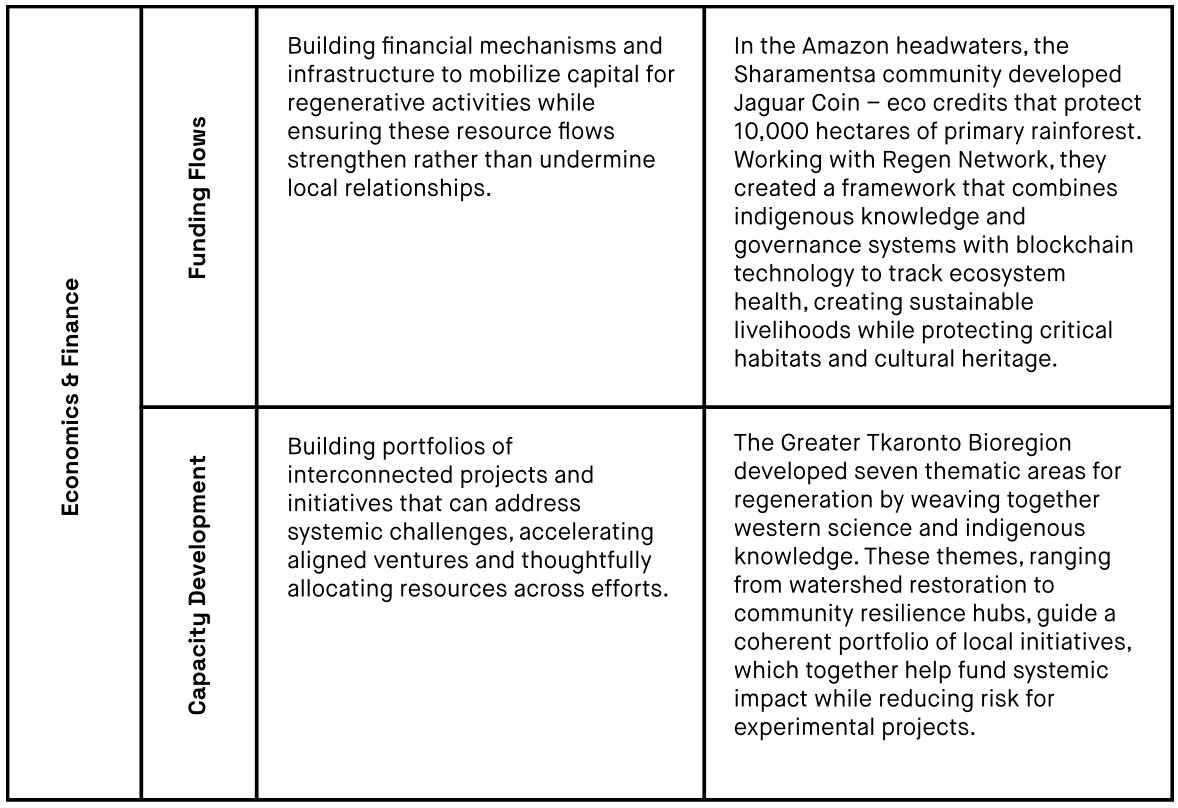

While early-stage organizing teams might focus on basic community building and knowledge gathering, mature teams develop complex systems for governance, strategic development, and financial management. The table below details how some of these key organizational processes manifest, particularly in more mature bioregional efforts:

This process-centered approach allows us to learn how to create life-enhancing social systems informed by ecosystem processes in place. Since transformation moves at the speed of trust, the most crucial element of bioregional organizing is building the social capital and relational capacities that enable genuine collaboration. Teams must demonstrate sustained commitment over time to build the legitimacy needed for deep systemic change.

Blockchain technologies act as a critical enabler by providing a sandbox for experimenting with new institutional components in action. Communities are using these tools to create eco-credits that generate sustainable funding flows, track and reward community contributions to regenerative activities, enable participatory budgeting for local projects, and develop new kinds of nature-driven governance structures. These experiments provide the building blocks for new systems to take shape.

At a deeper level, blockchain’s influence extends beyond technology to how we think about coordination itself by highlighting the power of protocols as flexible frameworks for collaboration. Protocols provide just enough structure to enable cooperation while maintaining adaptability, whether they are computer code managing digital transactions or social agreements governing shared resources. Like traditional commons management systems, they create a clear set of rules that communities can enact without imposing rigid hierarchies.

This protocol thinking offers powerful new models for fractal, cosmo-local relationships between the globalized world and local communities. Common protocols enable coordination across scales – supporting nested governance between cities, ecoregions and bioregions – while preserving local autonomy. This mindset also allows successful organizing protocols to act as a shared social infrastructure that can be shared across bioregions, while remaining deeply responsive to each unique context.

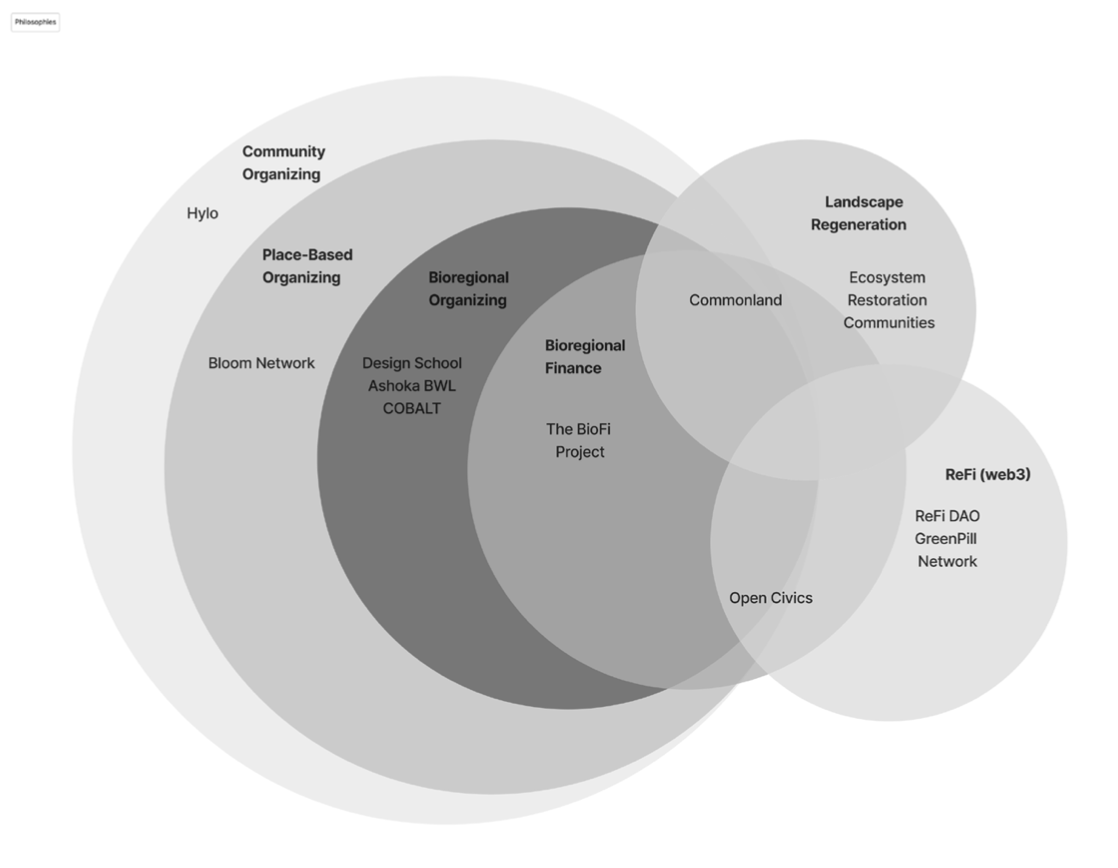

Learning networks play a crucial role by stewarding these common social protocols - facilitating relationships, developing shared knowledge, and enabling resource flows across the movement. Rather than organizing specific bioregions, these groups support the broader ecosystem of bioregional organizing teams. Through this higher-level coordination function, they drive the movement’s growth and development.

Learning networks offer different approaches, areas of expertise and value systems. This plural diversity is a key strength – by exploring multiple directions simultaneously, the movement uncovers a fuller range of possibilities. For instance, Hylo’s broader community organizing scope has helped channel resources that might otherwise be unavailable within a stricter bioregional frame. Similarly, ReFi DAO’s approach to impact measurement and capital allocation mechanisms is able to appeal to traditional sustainability fields, opening pathways toward bioregional thinking.

The diagram below illustrates some of the key learning networks in the movement, along with their core focus areas.

Through the dedicated work of bioregional organizing teams and the networks that support them, the infrastructure to enable systemic transformation is being built today. Together we are re-learning through practice how process-centered, fractal and plural principles can be embodied in how we organize ourselves.

This ecological embeddedness uncovers new approaches to ongoing crises like Barcelona’s water supply. Rather than treating the water as a mechanism to be engineered, we could organize around watersheds, understanding deeply how water moves through our landscape. This means creating governance systems that incorporate the voice of the watershed itself, developing financial models that enable long-term investment in ecosystem regeneration, and building community processes that help people understand and steward their relationship with water.

But this transformation requires more than just good ideas – it requires the patient work of building new organizational capacities and ways of relating. Through the growing ecosystem of bioregional organizing teams and the learning networks that support them, we’re developing the social and technological protocols needed to reorganize human activity around ecological rather than political processes. By strengthening how these groups learn and work together, we can help catalyze the deeper shift in how human communities relate to the living systems that sustain us all.

Back to Table of Contents | Next: Third Interlude | Previous: Walkthrough of the Green Crypto Handbook

Footnotes

-

“Idea Machines,” https://nadia.xyz/idea-machines. ↩